‘Can You Imagine This World Without Forests?’

The late Dr. Sandra Brown of Winrock spent her long and accomplished career making sure that question remains rhetorical.

By Chris Warren

**Dr. Sandra Brown passed away at her home in Wales on February 13, 2017. Winrock International joins her family, friends and professional colleagues in mourning her loss. Please click here for an obituary.**

**Dr. Sandra Brown passed away at her home in Wales on February 13, 2017. Winrock International joins her family, friends and professional colleagues in mourning her loss. Please click here for an obituary.**

The issues being discussed in the Guyana Forestry Commission’s (GFC) sparsely decorated, wood-paneled conference room are complex and consequential, yet Senior Scientist Dr. Sandra Brown — who spent almost two decades doing groundbreaking work with Winrock — seems borderline giddy. Seated behind desks that have been pushed together into a horseshoe formation, Brown and a team from Winrock’s Ecosystem Services Unit quickly delve into some weighty topics with their GFC counterparts. In particular, there are questions about what to do now that a landmark Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) deal between Norway and Guyana has ended.

Winrock played a central role in developing the monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) system Guyana used to earn nearly $200 million in payments from Norway for limiting deforestation and forest degradation — an arrangement that both curtailed carbon emissions that result when trees are cut down and provided Guyana much needed capital to help foster a green economy. Also on the meeting’s agenda are more technical questions about how to account for carbon emissions in sections of the forest near areas cleared for mining and how to assess land that switches from agriculture to forest and back again.

Throughout the hours-long, often detailed back and forth, Brown is at the heart of the conversation, her hands constantly in motion and frequently punctuating her points with a rhetorical, “do you know what I mean?” When a break for coffee and restroom visits drags on too long, she claps her hands and says, “OK, class,” with the authority and ease of the former university professor she is. By the end of the day Brown is, if anything, more energetic than when the meeting first started. “See how much fun science can be?” she declares to the room, a smile animating her face.

A career exclamation point

The fact that Brown is so happy discussing what can strike the untrained ear as arcane details about the carbon levels in the Guyanese forest is hardly surprising. After all, understanding and quantifying the connection between the world’s climate and its tropical forests has been the focus of Brown’s career since 1979, when the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) funded her first research projects. Since then, both as a university professor and as the longtime head of Winrock’s Ecosystem Services team, Brown has been at the forefront of not only understanding how much carbon is emitted when forests are cut down, but also helping countries develop and implement strategies to preserve them.

“She is one of the pioneers of the whole field of carbon accounting and tropical forestry,” says Katie Goslee, a Winrock program officer who has worked closely with Brown in Guyana and other countries. Indeed, not only has Brown led over 50 global projects related to land use and climate change, but she has also been an astonishingly prolific scholar, authoring or co-authoring over 200 peer-reviewed papers. When former vice president Al Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, Brown received a diploma to recognize her contributions to the group’s work.

Still, after a career of impressive accomplishments — Brown joined Winrock in 1998, after nearly two decades as a professor at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana — the six years of work in Guyana rank as the most personally satisfying. In part, that simply has to do with the role she has had. In 2014, Brown relinquished her position as the director of Winrock’s Ecosystem Services team to become a senior scientist. The change in titles was meaningful, allowing her to spend less time on contracts and budgets and more time marinating in the science and the numbers. “I actually get in there with the data. That’s what I like to do,” she says. “I’m basically a scientist at heart.”

It helps, too, that the work in Guyana, where forests cover 85 percent of the country, has yielded real-world results. Besides helping Guyana live up to its REDD+ obligations, Brown and her team assisted in developing its forest reference level — basically an estimate of historic emissions from timber harvesting and other activities that serves as an important benchmark to measure future changes — to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). By becoming the first country to submit a reference level to the UNFCCC that included forest degradation, Guyana cemented its position as an international leader in REDD+. “It went through all of the reviews, multiple reviews in the UNFCCC,” says Brown. “They think it’s an excellent piece of work.”

Still, for a consummate scientist like Brown, perhaps the best part of the work in Guyana is that she learned something new. What she discovered — and then double-checked when a UNFCCC reviewer questioned it — was that Guyana’s forests contain trees with such dense and hard wood that they contain phenomenally high amounts of carbon. “I thought I knew all there was to know about carbon stocks in tropical forests,” says Brown, the excitement building in her voice as she describes the epiphany. “The results were eye-opening.”

An unlikely path

By no means was it predestined that Brown would become the rare scientist that autograph seekers track down at international climate change conferences (true story). As a kid growing up outside of London, Brown learned to appreciate the natural world, though mostly at a playground where she could spend her afternoons traipsing through the woods looking for birds, animals and adventure.

Once in school, though, Brown gravitated to the arts and humanities, cultivating a special fondness for the French language. But she was scolded when she informed one of her teachers about her plans to continue along that academic path. “She said, ‘you should take chemistry, physics, mathematics, you’re good at that,’” Brown recalls. “She’s my teacher, what do you do? You follow their advice. So I did.”

With that blunt encouragement, Brown opted to study chemistry at the University of Nottingham. Though she majored in chemistry, Brown says she also garnered some valuable life lessons about priorities in school as well. “I didn’t know the difference between having fun and working,” she recalls. “So I learned a few lessons there.” Nevertheless, Brown’s affinity for play didn’t prevent her from earning a degree and taking a job teaching high school science in London. While teaching in the British capital, Brown met an American and the couple got married and moved across the Atlantic Ocean to St. Petersburg, Florida, where she landed another high school teaching job. There, the trajectory of Brown’s life began to change after a number of her students left to attend the University of Florida and she became aware of the school’s Department of Environmental Engineering. “I thought it sounded fascinating,” she recalls.

Enrolling in a Systems Ecology Ph.D. program at the campus in Gainesville, Brown quickly felt out of her element. She vividly recalls a biology course she took — the first one she had taken since she was 12 years old — where the scientific vocabulary thrown around was so beyond her (“I didn’t even know what a cell was,” she laughs) that she would write the long words down during class and look them up in the dictionary afterward. It wasn’t Brown’s only challenge. For someone studying systems ecology, Brown had an extremely inconvenient fear of spiders. “I worked in swamps with big spiders in these big webs. And I always took a young person, a student assistant, an undergraduate, and I said, ‘OK, you blaze the trail today through the swamp and knock down the spider webs.’”

Pioneering work

Learning to persevere and, when necessary, face her fears was important once Brown earned her Ph.D. and started work as a researcher and academic. As she was finishing up her studies, a colleague at the University of Florida asked her to help write a proposal to the DOE to investigate the role of tropical forests in the global carbon cycle. Though it was the late 1970s, long before public awareness was raised about the reality of climate change, the DOE knew all about the connection between carbon emissions and a warming planet and figured that it would eventually have a role in regulating greenhouse gases. To do that well, the DOE realized it needed to have a better understanding of the sources of carbon emissions.

The DOE was especially interested in emissions from tropical forests because a paper had come out in the academic journal Science that had implied that more carbon went into the atmosphere as a result of cutting down trees than burning fossil fuels. Brown was well suited to investigate (and eventually debunk) this claim because her Ph.D. involved quantifying how much carbon was in the swampy forests of Florida. At the time, though, Brown and some other colleagues who were investigating carbon levels in tropical forests came to realize just how little data and knowledge was available. Examining all of the existing scientific literature led Brown to the realization that estimates of global carbon stocks around the world were based on measurements of just 30 hectares of land. “Less than 30 hectares and we are going to make these big extrapolations?” Brown remembers thinking. “Oh, no, we can do better than this.”

But doing better wasn’t always easy. Understanding that accurate estimates of forest biomass was critical to gauging carbon levels — not to mention emissions that occur when trees are cut down — eventually led Brown to spend countless hours in the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations library in Rome, Italy. She knew it was where she could find what are known as forest inventories of countries around the world. “Often they call it a pre-investment inventory, where they want to know how much timber they have in a given forest,” says Brown. Boxes upon boxes of this sort of data were available in Rome, and Brown methodically went through everything available for tropical countries.

All of this sleuthing yielded data about the total cubic meters of timber in tropical forests, helpful information to timber company executives but not necessarily something Brown could use. “How am I going to convert this to biomass?” Brown remembers asking herself. The answer was to develop what are known as allometric equations, which take simple indicators to obtain a more elusive measurement. For instance, an allometric equation could use a person’s height and waist size to estimate weight.

Brown did more or less the same thing with trees, using measurements of their diameter and density to estimate biomass and, ultimately, carbon. “This is how I started developing these equations,” she says. So pioneering were these equations that the FAO asked Brown to put together a book about how to estimate the biomass of tropical forests. “It sold out very quickly,” she says. Though Brown’s original equations are no longer widely used, they are still referenced by researchers and have served as important building blocks for more sophisticated tools to estimate carbon stocks in tropical forests.

As much as Brown had strived for a career in academia, she also came to understand that it had its limits. The opportunity to put the tools she did so much to develop to practical use ultimately led Brown to Winrock. “Academia was always a bit of a struggle for me because it was a bit too theoretical. You want to see you made a difference,” she says. “Winrock provided that opportunity. The way we developed the Ecosystem Services Unit was with good science, but dealing with real problems related to forests and climate change.”

A woman in a man’s world

These days, Brown’s pioneering work is recognized globally. But basic respect, let alone acclaim, wasn’t always the norm. Pursuing a career in science as a woman in the 1970s was not always easy. Though she doesn’t think she lost out on jobs because of her gender, there were times when she was treated differently. As the only female professor in the University of Illinois Forestry Department, she had to listen to blatantly sexist comments from male colleagues. “They used to have meetings in my office, and they’d always say, ‘Well, Sandra, do you have the coffee and donuts?’” she says. Brown says she would brush off the comments with a joke. But she still remembers them today.

More troubling to Brown than sexist barbs about donuts and coffee, though, is being described as aggressive and outspoken. While men are hailed as leaders for speaking bluntly, Brown says she has been criticized (usually by men) for doing the same. “That has annoyed me through a lot of my career because it’s like, come on, guys, you should be able to speak out,” she says.

Part of being a pioneer is encouraging others to follow your lead. Throughout her career, Brown has made it a point to encourage more women to pursue careers in science. Today, when she gives public presentations, she always recognizes when there are a lot of young women in the audience. As a professor, she would dress stylishly when she was giving lectures as a way to provide an example to her female students. “I wanted to get across the message that you can be in forestry and still be a woman,” she says.

At Winrock, Brown has been particularly eager to mentor female staffers. “She considers herself a mentor and wants to be a mentor to people, and she is,” says Katie Goslee. “I have learned a lot from her.” In part, this has been a way for Brown to encourage younger colleagues, both women and men, to strive to do good work. But she also understands that it’s a way to ensure that Winrock continues to be at the forefront of REDD+ issues. “What’s a good reflection of your career? It’s your students or your mentees,” she says.

Given how few women were in science when she first started in her career, it is perhaps appropriate that women have spearheaded the vast majority of work in Guyana. Not only is the effort led by Pradeepa Bholanath, who is head of the planning and development division of the GFC, but women handle everything from monitoring satellite data for changes in the forest to spending weeks in remote camps collecting field data. Bholanath says Brown’s example as a strong and capable leader has made a big impact on her and her staff. “She is, to me, a role model for what women can do once we do not get caught up in these boundaries that may have existed for decades,” she says. “She has really opened up our eyes to what we are capable of as women in a field that is male-dominated.”

Not just about the data

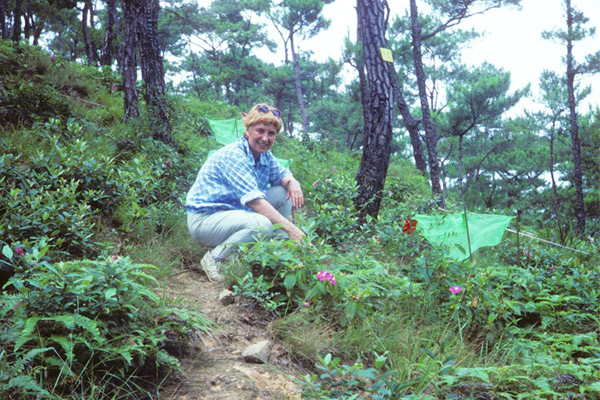

A plane flight and a bumpy ride away from the conference room in Georgetown, Brown is walking across a carpet of dry leaves on the forest floor, pitching in as a team from the GFC measures trees, that essential step in determining the carbon stocks of a forest.

Located outside of the mining town of Bartica, nothing about this particular chunk of Guyana’s sprawling forest is uniform. The tree sizes and species are varied, an indication to Brown that it’s used for many purposes, including selective logging. And that’s just fine. “It’s a resource that developing countries have, and it’s a way for these countries to develop,” she says.

The trick, of course, is to do it responsibly and sustainably, something that arrangements like the REDD+ deal between Norway and Guyana could make easier. Even though Brown has spent her career thinking about forests and carbon — and has helped lay the foundation for REDD+ — she doesn’t just have data and carbon sequestration on her mind on this muggy, overcast day in the forest. The need to preserve and wisely manage the world’s forests extends well beyond science.

“They’re something we need for our spirituality, for our feeling of well-being,” she says. “Can you imagine this world without forests? Can you imagine not being able to go to a forest? No. It would be a terrible earth. Terrible. We just need forests.”

Related Projects